(Constructive Disobedience: Feldenkrais ® in the Yoga Classroom was originally published in May 2012. I offer it here as part of a series of favorites pieces I am updating for my new website. For another article on Feldenkrais in the Yoga Classroom, see my article: Lodestones of Sensation)

Feldenkrais in the Yoga Classroom

There is a delicate duet we dance in the yoga classroom. How do I, as a teacher, lead without stepping on my partner’s (my students’) feet? If it is my goal—and it is—to encourage my students’ personal development along each one’s own path, how do I do that in drop-in classes at an urban yoga studio? How do I provide for each individual’s unique process—her unique sense of time, learning styles, interests, and all the things she brings into the classroom of which I have no knowledge? In the authoritarian teaching model we have inherited, (and which serves a purpose; it is orderly and serves many at a time), how do I acknowledge each student’s autonomy? Her precious selfhood?

Our material in yoga is not movement, but one’s experience of the self in movement. How do I help my students move through the movement material I offer them to that deeper place of self-inquiry? How do I help them experience themselves inside the movements, and experience the movements as their own? The Feldenkrais Method of Somatic Education® has given me many tools to work with, but the yoga classroom is not a Feldenkrais classroom. While the two share some goals—like yoga, Feldenkrais is an awareness practice in which we come closer to knowing our true selves through self-observation and refinement in movement—there are some distinct differences.

Students coming to yoga expect to move, stretch, and experience some intensity of sensation. (In Feldenkrais we move small and slow, to experience the subtler sensations.) Many yoga students prefer to use their eyes for learning movement, watching a teacher at the front of the room lead them through the yoga poses. (In Feldenkrais, instructions are verbal, not visual.) In yoga, we ask the teacher to carry us along energetically through a series of challenging poses, and to pace our movements like a choreographer or a dj. (Feldenkrais students move at their own pace, doing as much as they choose, and resting when they choose. Feldenkrais teachers watch their students for cues about class pacing.) Excluding gentle and restorative classes, yoga classes are generally expected to be challenging, delivering us beyond our limitations. (Feldenkrais classes cultivate effortlessness in movement. Students often practice in reclining positions, and rest regularly.) These are generalizations, and many yoga classes share Feldenkraisian qualities, but I believe my description above holds versions of truth.

I have taken it as my challenge to use some of my Feldenkrais tools in the yoga classroom. My goal is to “walk the walk” better. If I really am interested in cultivating an environment in which your learning path is not the same as the path of the student on the neighboring mat, I need to do so in whatever ways I can. For a while, I stumbled around applying the wrong tools at awkward times for reasons of which I was unclear. Now, I am beginning to find adaptations and creative solutions that honor the positive qualities of the yoga classroom and serve the students I have before me. One example follows.

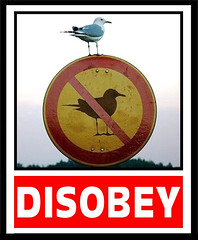

Practicing Constructive Disobedience

Throughout January and early February 2012, we made constructive disobedience our explicit practice in all my yoga classes. In constructive disobedience, we stay present with what is happening in class, but we take the instructions of the teacher as invitations, not as commands, so there is space for us as individuals to make choices. Another way of saying this is, “I am the queen/king of my kingdom.” or “I am the lord of my dominion.”

I begin class by enunciating our constructive disobedience practice clearly, making eye contact with my students, and pointing to a little poster I have taped above the alter where the words are written, “I am the queen/king of my domain.” (I mean business!) I talk about how I cannot know your (my student’s) experience. I am well trained and intuitive, but I am not you. Only you know what’s happening inside you. Practice being constructively disobedient, even if it means doing something different than what everyone else is doing in class. When you need to rest, rest. You may rest in child’s pose, in standing, or in any other comfortable position. You may kick back and lie over bolsters for the remainder of class if you want to. You are the lord of your dominion. If you need to adjust a pose to make it more comfortable, do so. If you need some ideas about how to adjust, look around the room and see what others are doing. You may call out and ask for help from me. Make this class work for you.

In order to prepare for this practice, our first movements are “choice time”. After we sit and focus our attention, I ask the students to lie on their backs, and take the next two minutes (or some clear measure of time) to move in any way they wish. I encourage them to ask, “What does my body want right now?” This begins class with deep listening—ask a question, and listen for a response in the form of sensation, desire, image, or impulse. I sometimes make suggestions if people look lost: “Maybe there’s some part you want to stretch, or maybe it would feel good to roll side to side. Some of you may want to just rest on your backs and listen to your breath.” This is a very small gesture toward self-governance, but it is a very long two minutes for some. Many welcome it, while others anxiously wonder what to do. All are meeting themselves in the process. When I offer “choice time” again at the end of class, there is no anxiety, just self-sensing.

During our asana (yoga poses) practice, I offer choices as often as I can without making the instructions so muddy that students get lost. I take time for this; my class does not flow in one rhythm from beginning to end. We often simply stop to sense ourselves. During rests and during movements, I refer regularly to the students’ experiences, “What do you sense?” “Do you notice a difference?” “Observe your breath.” “Observe the pressure of your feet in the floor.” “Sense your bones.” “Follow the pathway of… (your right foot, your tail bone, the back of your heart).” All of these cues encourage deep listening. When I see my students pushing too hard, I don’t say, “Don’t push,” as often as I used to. I say, “Is it enough?” “When are you done?” “What’s the just right amount of effort for you right now?” I am asking them to take some responsibility for their own experience. I still hold the container. I lead them through movements, rests, observations and partnering. But there is give and take between us. As in a truly great duet, the dance emerges in the middle space between leader and follower.

Constructive disobedience is the ground on which all my classes stand. My students still need gentle reminders to do less following and more self-inquiry. When I make that reminder, there is always a sense of a deep sigh in the room. The bodies get a little heavier, the feeling-tone gets lighter, and activities diversify. Ironically, there is a greater sense of shared experience in the room when this happens. We are all on our own individual paths—together.

(This article was originally published in 2012)