An Invitation to Pleasure

“Move toward pleasure,” a dance teacher once offered us young dancers. It was a novel instruction and the results were stunning. I felt a patience and kindness toward myself I had never felt before, and movement just poured out of me. The whole group seemed to wake up and slow down at the same time. We were cultivating a new kind of relationship with ourselves and our movement, one in which we trusted our ability to sense, perceive and respond as a source of movement, rather than straining against an idea of good performance.

That moment in dance class was so transformational for me, I looked for ways of bringing the idea into my own teaching, and I’ve been teaching my students to “move toward pleasure” in my dance, yoga and Feldenkrais® classes since. It can be awkward for some students to hear the word “pleasure.” And what does it mean to move toward it? I can feel the reaction in the room sometimes—a kind of bewilderment, or resistance, and the holding of breath. I will often add more to clarify, for example: “What if there is no right way to do the movement, except that it feels good to you?” As students get more clear about what I am asking, I will often notice a kind of relaxation move through the group—like in that first dance class years ago—a letting go of the bracing and armoring that accompanies us daily. Most visibly breathe better.

What is that moment of resistance about, that moment of holding breath? One explanation may be that it is taboo in our culture to experience physical pleasure in other than prescribed ways, especially in public. Some may not be used to allowing themselves physical pleasure in any context. Also, for some, the instruction to move toward pleasure asks them to soften a shield unconsciously put up to protect against historical or present trauma. (For an interesting discussion, see My Grandmother’s Hands, by Resmaa Menakem.)

I will sometimes ask students to brush their hand along their leg with no purpose but to drop them into sensation. They begin to touch themselves in a soft, receptive way. This can potentially challenge those taboos and protective shields, and I am always careful to watch for discomfort. I am inspired and moved every time I see someone allow themselves this receptive self-touch, or when I hear an audible sigh that signals the letting go of bracing tension. It is a privilege to witness these tectonic changes. Every bit of letting go, opening, or releasing is potentially a personal triumph on a planetary scale. Even the smallest moments of self-regard deserve great respect.

Articulating pleasure

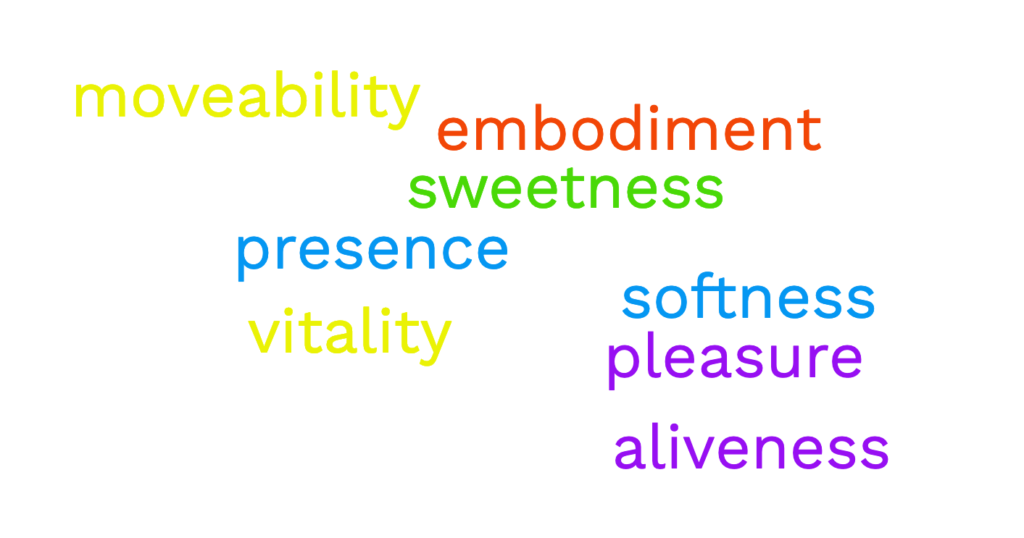

As I came back to the theme of pleasure some years ago, I wanted to freshen my views a bit, so I went to a master on the subject. Reggie Ray’s book, Touching Enlightenment is a lodestone for me. I started to collate some of Reggie’s words into lists. I posted these words for my students:

These words help to clarify the profound gifts that moving toward pleasure rewards us with.

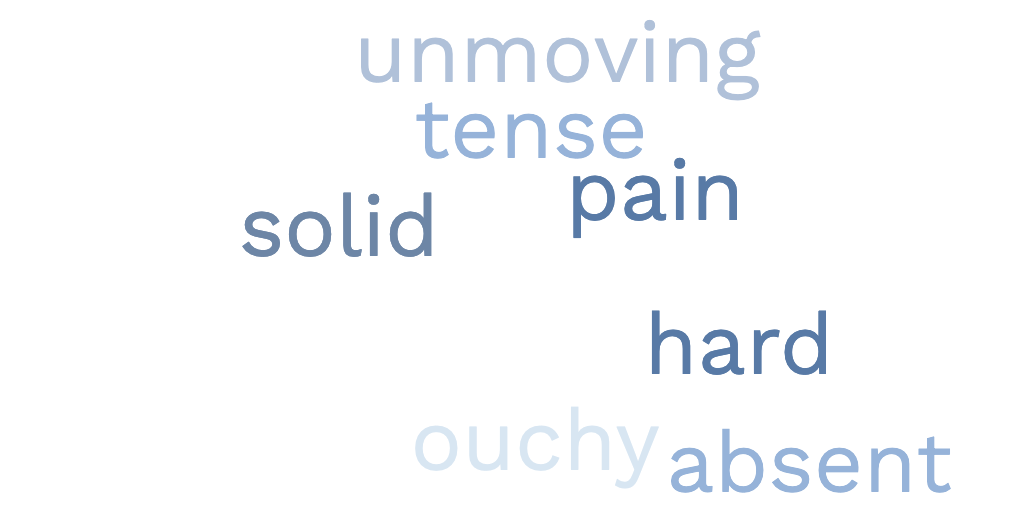

On the wall next to the pleasure words I put pain words. Ray describes all these physical sensations as embodiments of pain:

Pleasure and pain are on opposite ends of a continuum of mindbody experience.

There was a moment, those years ago, researching about pleasure, when I was halted in my preparations, stunned that I had been so blind to a fundamental problem in my teaching. I realized that if one experiences any pain—and most of us do—pleasure is a far country to reach! To invite someone in pain to head straight to pleasure may be setting them up for failure. “How can I move toward pleasure if I can’t stop thinking about this damn pain!?!”

Pleasure and pain, what else is there?

Concerned that I might alienate some of my students by thrusting them toward the impossible, I made another list. This is a list of neutral sensations or experiences that lie somewhere in the middle of the pleasure-pain continuum:

Neutral

Moving—Still

Cool—Warm

Long—Short

Dense—Spacious

Smooth—Rough

Loud—Quiet

Pressed Upon/Constrained—Free to Move/Unconstrained

Symmetrical—Asymmetrical

Wobbly—Steady

Clear—Fuzzy/Foggy

Effortful—Free

Staccato—Legato

All at Once—In Sequence

Paired with—Unpaired/Independent

What Position (organization of body parts)?

What Orientation (organization of self in space)?

What Path (direction of movement in space)?

What Point of Initiation (from where the movement begins)?

… and any sense of “This is Different from That”

The neutral list keeps growing. Years ago, I added to it every time I taught, and even now, as I write, I am finding new ones. Some of us are synesthetes; we experience tone, color, timbre and texture in our physical sensations, qualities that are generally associated with sound, vision and touch. Some experience that parts of the body speak or have stories in them. Some move through images that are metaphors from everyday life or from fantastical realms. Others experience sensation as affect or abstraction. Any way of experiencing is welcome when considering the list of neutral sensations.

The neutral list is so important, because it is the gateway from pain to pleasure. We may balk when asked to focus on pleasure while we are in pain, but we can usually find our way to some neutral sensation somewhere in the body. An interesting thing happens when we rest our attention in a non-judgmental way, without expectation or ambition, on our neutral sensations. Our bodily experience becomes dimensional, unfixed, and responsive to our inquiry. Calm, spaciousness, curiosity about ourselves, and, eventually, pleasure creep in.

Why do we have pain?

Why does this process seem so elusive? Why don’t we naturally attend to neutral and pleasurable sensations if they’re so good for us? Because the process of evolution selected for an acute ability to sense pain. Nature needs for us to get to the age of procreation, so it gave us very compelling pain sensations to help us avoid catastrophic injury.

Initially, pain is there for a reason, to alert us that some harm has come to our organism that might threaten our ability to stay alive. When I say the sensation is compelling, I mean it attracts and holds our attention, like a good movie (or, like a toddler having a tantrum); but there are some inefficiencies in our design. A pain can be so compelling that it echoes throughout our nervous system even when the mortal danger has passed. Natural selection doesn’t mind about that, as long as our organism remains intact and functional for procreation.

Scientists are now finding that our central nervous system can actually be damaged by pain signals that run for long periods of time, creating a cycle where mistaken messages of pain continue even after injury has been healed. While that initial pain was there for a reason, some of this residue pain is just confusion. But it’s pain, so we keep getting these messages that draw our attention and yell, “Alert! Alarm!” (For an excellent discussion of this, see Chapter 1 of The Brain’s Way of Healing by Norman Doidge, and the work of Adriaan Louw)

Freedom Through Neutral

Most of us live quite a bit longer than our reproductive period, yet we’re given this body that is designed to prioritize procreation, not everlasting comfort. The pain mechanism is powerful.

How can we live not just long, but well? Nature has selected for another characteristic that can help us out of this mess: conscious awareness. We can willfully direct our attention away from dysfunctional pain (pain that is no longer serving its purpose to keep us safe), toward neutral and pleasurable sensation. Because the nervous system is plastic, meaning changeable, we can actually strengthen and build more neutral and pleasure pathways throughout our nervous system by choosing to attend to those sensations, rather than being trapped by the dysfunctional pain cycle.

I want to be clear here that I do not advocate denying pain as a way of bucking up and getting on with life. I am talking about opening a door to a range of experience that includes and goes beyond pain. Many of us (I include myself here) who experience chronic pain have a tendency to identify ourselves with our pain and with our conditions. (I am a Migraineur!) We become frenemies with our pain—it keeps us company, entertains us, holding our rapt attention, even as we despise it. I can say with confidence that if I did not have the muscle, built up during years of practice in dance, meditation and the Feldenkrais Method®, to attend to the world of sensation beyond pain, I would have followed my pain down the rabbit hole, never to return, long ago.

Training my attention on neutral and pleasurable sensations, even during migraine, can decrease my pain level. More importantly, by opening that door to sensation, I become much more than my pain. I am living, breathing, sensate, and full of curiosity about my human condition. I am myself, experiencing pain as one of many temporal experiences.

Training our attention on neutral and pleasurable sensations while not in intense pain benefits us in a similar way, and also flows easier, feels richer, and develops in us a strength that supports us in more difficult times. And so, when we practice moving with awareness, in Feldenkrais, dance, yoga or other modalities, we may move our attention toward many sensations, not allowing ourselves to be held captive by just one kind. This way, we just may find that our movement practice is life-giving and nourishing, and we may accept the invitation to move toward pleasure without reservation.